"Well, if it's a symbol, to hell with it," Flannery O'Connor said and silenced a room of NY intellectuals. This Exclusive Writing Lab explores how a sharp-witted Georgian created literature that still unsettles readers sixty years after her death.

Welcome into Flight School:

Before we get started, I’d like to announce:

The Second Annual Get-it-Done Summer Challenge

When: June 1 to July 15.

What: Six week challenge with daily interaction and bi-weekly live Zoom calls.

Why: This challenge, like all the Flight School challenges, is designed to inspire and motivate.

Stay the course on your writing schedule

Jump start a flagging project

Finish something that you’ve need to push across the finish line

I’ll be finishing my own novel, The Home Tree, in our time together. Last year, I worked the draft and it was great. This year, let’s do it again.

Save the date and I’ll get you more deets over the next couple weeks!

Let’s get it done.

The first time I read Flannery O’Connor, I did not care for her work. It was too intense, too “in your face,” too raw. Now, I’m older, a revert back to Catholicism after many years away, and a writing teacher, I find she is the most honest writers I’ve had the good fortune to read. It’s not a stretch to say she is also one of the most important writers of our time.

Thomas Merton, author of The Seven Storey Mountain, compared her, not to contemporaries like Hemingway, Porter, or Sartre, but to Sophocles, “…for all the truth and all the craft with which she shows man’s fall and dishonor.”

Elizabeth Bishop wrote: “I’m sure her few books will live on and on in American literature. They are narrow, possibly, but they are clear, hard, vivid and full of bits of description, phases and an odd insight that contains more real poetry than a dozen books of poems.”

For those unfamiliar with her work, O'Connor's prose hits with brute force:

From A Good Man Is Hard to Find, the famous line from the Misfit reflects on the grandmother: "She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life."

From Revelation, when Mary Grace attacks Mrs. Turpin: "The girl raised her head and directed her fierce brilliant eyes at Mrs. Turpin. She had a peculiar face, highly colored and unnaturally red, as if its skin had been bound too tight."

From Everything That Rises Must Converge, the moment of Julian's realization at the end: "The tide of darkness seemed to sweep him back to her, postponing from moment to moment his entry into the world of guilt and sorrow."

And it’s not just her stories. If you can get your hands on her letters, do it. My favorite is The Habit of Being. The pure truth, wit and grace of Flannery O’Connor will inspire you to unearth similar qualities that you might stifle in these times of “diagnosis” and exhausting self-editing that started with the political-correctness movement and have only accelerated into madness during this current “misinformation” era. A woman can’t speak a single line without double checking who she’s offended.

I say bring back the honest woman, and perhaps that’s what you’ll find in this excellent writer and thinker taken from us too soon.

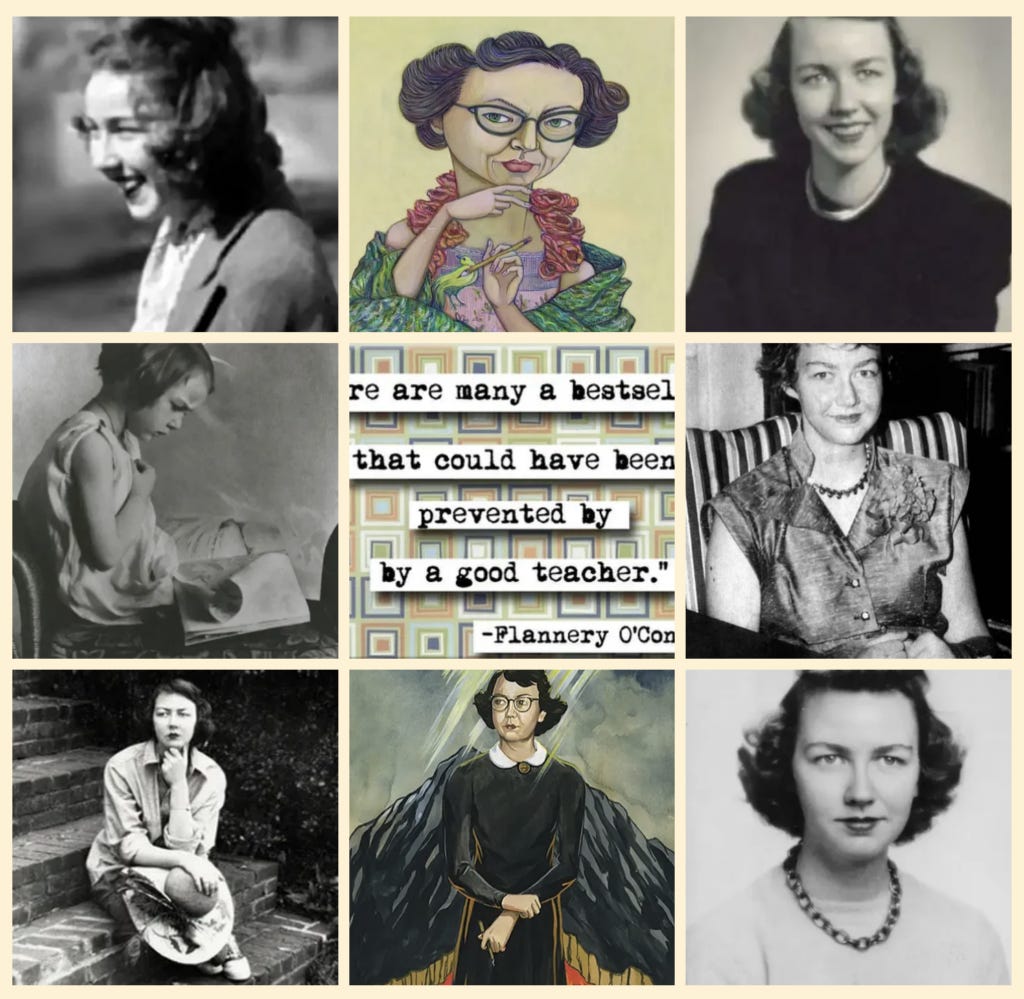

“Everywhere I go, I’m asked if I think the university stifles writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.”

~ From a letter O’Connor wrote to her friend “A” (Betty Hester) dated February 8, 1958, The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor, edited by Sally Fitzgerald.

Mary Flannery O’Connor was born in 1925, in Savannah, Georgia. This year, she would have been a hundred years old, and we would have a library of brilliant writing to show for it. Instead, we have a tight, concise, and amazing collection of works created in her short but productive time on earth. O’Connor died of complications from lupus in 1964 at age thirty-nine. Despite her illness that confined her to her family farm in Milledgeville, Georgia for much of her adult life, she produced two novels, almost forty short stories, and numerous essays and letters.

O’Connor as Artist

O’Connor’s artistic vision was singular and uncompromising, her fiction characterized by gothic elements and southern settings, grotesque characters and violent revelations. She wrote sharp, economical prose rife with dark humor and shocking plot twists.

Her dedication to revision was legendary. “I rewrite as much as I write,” she noted, evidence of her commitment to perfecting her craft that continued until her final days. Even as her health failed, she continued working. In the last months of her life, she mailed her publisher Robert Giroux Judgment Day and revised versions of The Geranium and An Exile in the East. She worked until she fell into a coma—a testament to her extraordinary commitment.

O’Connor as Catholic

“I write the way I do because I am Catholic,” O’Connor said about her work. “This is a fact and nothing covers it like the bald statement.”

She grew up surrounded by protestants and battled with bigotry and critics. More so when she entered the intellectual elite of creative writers. One famous incident was when O’Connor attended a literary dinner party in New York, likely in the late 1940s or early 1950s. At this time, O’Connor studied at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and spent time in literary circles in New York. At a gathering hosted by Mary McCarthy, a writer known for her secular humanism and sharp wit, McCarthy spoke of the Eucharist as a “symbol” she found “interesting.”

“Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it,” O’Connor said, silencing McCarthy and the room. Silent for much of the evening to that point, O’Connor explained that she believed the Eucharist was truly the body and blood of Christ, not merely a symbol. She would never be accused of watering down her faith for intellectual acceptance.

Her faith also manifested in her works, writing from themes of divine grace operating in the material world, of characters experiencing moments of revelation, often through violence or suffering and always, and ever more, focusing on sin, redemption, and judgment.

O’Connor’s work is never didactic or sentimental. She claws at theological concepts through stark, often disturbing narratives that will shake you to the core.

Going Against the Tide

While much mid-20th century American fiction embraced realism or modernist experimentation, O’Connor created her own distinct style that drew from Southern Gothic traditions but transcended them. She rejected pious, sentimental religious fiction in favor of stories that depicted grace in violent, disturbing ways. Though a Southern writer, she avoided romanticizing the South and instead portrayed its contradictions and failures. As a woman writer in the 1950s, she defied expectations by refusing to write domestic fiction or romances, instead creating dark, theological works populated with complex, often unlikable characters.

One of O’Connor’s most remarkable qualities was her absolute commitment to her vision, even when faced with editorial pressure. A revealing exchange with a publisher regarding the first nine chapters of Wise Blood makes the point:

The editor wrote to her, calling her a “straight shooter” with “an astonishing gift,” but suggested that aspects of the book were “obscured by her habit of rewriting over and over again.” He added that he sensed “a kind of aloneness” in the book, as if she were writing out of her own limited experience, and wished she would “sit down and tell him what was what.”

In response, O’Connor wrote to her friend Miss McKee: “Please tell me what is behind this Sears-Roebuck-Straight-Shooter approach. I presume…either that the publisher will not take the novel as it will be if left to my fiendish care (it will be essentially as it is), or that the publisher would like to rescue it at this point and train it into a conventional novel… the letter is addressed to a slightly dimwitted Campfire Girl and I cannot look forward with composure to a lifetime of others like them.”

To the publisher himself, she wrote: “I can only hope that in the novel the direction will be clearer…I feel that whatever virtues the novel may have are very much connected with the limitations you mentioned. I am not writing a conventional novel, and I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity, or aloneness, if you will, of the experience I write from…In short, I am amenable to criticism, but only within the sphere of what I’m trying to do; I will not pretend to do otherwise. The finished book, though I hope less angular, will be just as odd if not odder than the nine chapters you now have.”

Lessons for Modern Writers

Hold all feedback about your work with a light hand: Rather than seeking approval, seek ways to clarify your vision. IE: Get closer to nature. Be quiet. And most of all, re-write.

Stop suffering fools: Focus on your work, always and evermore. People might not get you right now, even in your own workshop. Your point isn’t be to be“understood” by everyone or even liked. It’s to be a better writer.

Commitment to craft: Despite her illness, O’Connor maintained a strict writing schedule and never stopped revising. When you are kvetching about time and challenges, remember O’Connor and create a manageable writing plan that plays the long game.

Embrace the unconventional: O’Connor’s work stands out because she refused to follow literary trends. Take heart. Create what is true and beautiful and the rest will fall into place.

Reading O’Connor Today

Over the next few posts, I’m going to do an analysis of three stories, Everything that Rises Must Converge, Revelation and A Good Man is Hard to Find. I’ll try to supply copies for each conversation but if I cannot, I suggest adding The Complete Stories to your library.

If you’ve not read her work yet, a few things to note:

She is not easy to read: Her stories make many uncomfortable (including myself when I first encountered her) but will never quite leave your mind. Approach with an extremely open mind and you’ll do well here.

Set aside knee-jerk and outraged reactions to her language: O’Connor’s Southern vernacular is part of her historical authenticity. Rather than judging it by cancel culture standards, consider it represents the true southern experience of that time and of those people. She was many things, but O’Connor was not a liar.

Read more than once: The depth and complexity of O’Connor’s stories reveal themselves through our reactions to them, the more intense the reaction, the more revealing of our own hearts and actions. She has defamiliarized language and storytelling in her collection and each rereading offers new insights.

O’Connor reminds us that great art isn’t always comfortable or easily digestible. It’s often challenging, disorienting, and profoundly unsettling—but ultimately transformative.

Your turn ✍️

What was your first connect with Flannery O’Connor? Share in comments. I’m listening.

Thanks for being with me for this terrific conversation, Jennifer 🐦⬛

Share this post