A Behind the Scenes post on Sarah Fay’s journey to publication, on how to hit (or miss) the zeitgeist, on punctuation as a memoir delivery device, plus a call to pick up the mic 🎙️ and share your own story of desire & disappointment

Welcome:

Sarah Fay sits in the seat of honor at my school, The Studio, where good writers become great because…well, she is great.

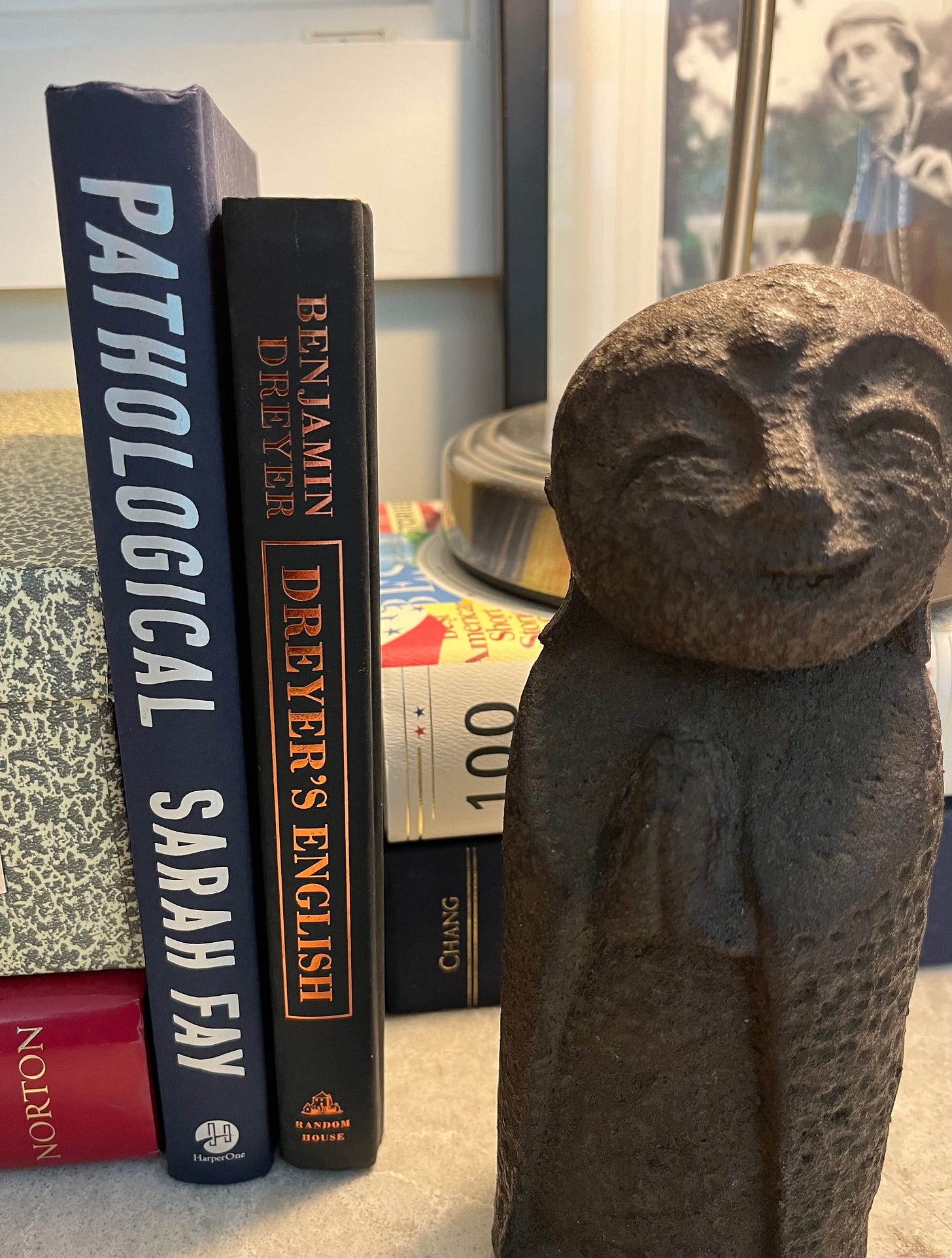

More specifically, her book Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses. Fronted by my happy monk and watched by Virginia Woolf, Fay’s work of art nests next to Dreyer’s English, Carl Jung’s Red Book, and 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories edited by Lorrie Moore.

Though the memoir details Sarah’s struggle with the widely used diagnostic tool, the DSM (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), and her heroic fight into and through a system that repeatedly misdiagnosed her, Pathological is also my go-to punctuation reference.

In the prologue, Sarah explains her “preoccupation with punctuation,” as incorporated throughout Pathological. “To many people, punctuation is a tedious part of human existence. But I’ve spent my life writing and reading and teaching people to write. Punctuation is the basis for communication. It’s how we form thoughts. It’s the mechanism behind our digital and written interactions, the vehicle that drives our connections and disconnections. Punctuation, like pathology, orders and categorizes; it tries to make sense of what’s otherwise disordered.”

This teaching is a brilliant move and one that permeates her memoir; innovative, tight lessons dropped in at times when readers need to rest their minds from the story itself…

Sometimes called suspension points, ellipses can be addicting. (People have been trying to prevent their overuse since the eighteenth century. 2) Once you start to use them to denote a falling off, an absence, or a dramatic pause, well…it’s hard to stop.

It’s teasing, how they imply more to come: There was no way of knowing what would happen next…

~Ch. 2, Pathological

Sarah’s main topic in Pathological is serious, even devastating at times, but along with teaching us punctuation, her writing is often laugh-out-loud-funny. Her wit,

dry and restrained.

It’s a book I recommend you buy and read.

Since reading Pathological last fall, I’ve wanted to feature Sarah in a way that is worthy of her gift. With her help, we’ve arrived at this post (previously featured in a slightly different format on her site) by way of introduction to a favorite conversation: Getting Published.

We all crave these stories because most of us crave publication, and yet…when we finally get what we desire…well, everything changes. Classic Sarah, she delivers heartbreaking honesty.

🎙️At the end, look for your opportunity to pick up the mic and share!

Guest post:

In my twenties and thirties, my big goal was getting a powerhouse agent and a six-figure book deal. I lived in New York—Williamsburg, pre-pre-pre-gentrification—in a basement apartment that leaked every time it rained. My job was as a writer-in-residence in the New York City public schools teaching students with severe physical and mental disabilities, often in economically deprived areas in the nether regions of the five boroughs. Riding the subway—sometimes three or four hours a day—being jostled by those around me, my regular practice was to imagine the moment when a powerhouse agent would call to say that she was two-thirds of the way through my manuscript and loved it and told me not to talk to any other agent until she could finish reading it and discuss representation. In true wanna-be-a-writer fashion, I hadn’t even written a book yet.

Twenty-five years later, on a dismal March afternoon at the start of the pandemic, I stood in my kitchen reading an email on my phone from just such a powerhouse literary agent. I had finally written that book, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses. The email from the agent was almost word-for-word what I’d wanted. Then, another e-mail pinged in. The agent was cc’ing her assistant to schedule a phone meeting.

On that phone call, I was told the manuscript needed no revisions (somewhat unheard of) and was ready to be shopped to publishers.

I signed with her.

She sold it in a month.

The afternoon my book went to auction, I sat on a bench in Lincoln Park, a flowering tree next to me, its branches fanning overhead, its pink buds beginning to open. Across from me was a bronze statue of William Shakespeare with a pink surgical mask over his mouth.

My cell phone rang. I fished it out of my bag and answered. My dream agent had gotten me a six-figure book deal with a dreamy big-five publisher.

Before you feel anything close to envy, let’s go over a few things:

I’d been a professional writer—publishing in The New York Times, The Paris Review, The Atlantic, etc.—for twenty years, struggling financially, mentally, and emotionally. (No Substack back then!)

I had three failed manuscripts (“failed” in the sense that I knew they weren’t my best work) in their deserved spot in an archived file on my computer that I’ve since trashed.

And despite what my (and perhaps your) fantasy-riddled brain may think, no lottery-winner-esque check arrives. Authors are paid the advance over three to four years, minus your agent’s commission and other publicity and miscellaneous expenses, which can be substantial these days. What’s left goes very fast when you’re trying to do things like, well, pay rent and eat.

In the park that day, I added up my accomplishments: I’d gotten the powerhouse agent and the book deal. I should have waved to Shakespeare, smelled the soon-to-be flowers, and strolled away with gratitude.

I’m ashamed to write this, but I didn’t do or feel any of that. At home, I drew myself a bath and sat in the hot water for a long time and cried. Eventually, my cat poked his head over the edge of the tub with a wide-eyed expression that said he still didn’t understand what all that water was doing there.

There’s nothing wrong with crying; what’s shameful is that my tears came not from joy but disappointment. I thought one of the other publishing houses at auction was more prestigious than the one that bought my book. How could I have felt disappointed at so much good fortune? I was extremely lucky, especially at that moment in history when people were dying and their lives were falling apart.

While things kept getting better, I became more desperate for whatever I didn’t have.

The pre-pub-date publicity run included a starred Kirkus review and an Apple Best Books pick. On the day of publication, Pathological debuted at number one in some obscure Amazon category. (Beware those touting themselves as “Amazon bestselling authors.”) One particular NPR interview resulted in a huge jump in sales, positioning my book in the vicinity of actual bestsellers. I got a TV spot. I was a guest on lots and lots and lots of NPR and other radio shows and podcasts. Pathological was featured in Oprah Daily and Forbes and many, many media outlets. And—the most coveted of all—The New York Times review was glowing.

But none of it was enough. Every morning, I’d walk around the lagoon and do my daily gratitude meditation, but it all felt forced. I wanted that NPR show and that TV spot and that bestseller list and those interview requests. That award and that mention and that review and that book club pick.

It’s taken me a long time to see that I wasn’t being awful; I was actually being very human.

There were so many unknowns. My publisher didn’t tell me how many books I was expected to sell, so I came up with a ridiculous number (700,000 copies).

And confusion. No one seemed to know how to sell my book or which media outlets would lead to a surge in sales.

And frustration. I was expected to do a large part of the publicity myself, which led to the hiring of not one but two independent publicists, one of which delivered two minor podcasts in exchange for the $24,000 I paid her.

Most of all, there was fear—a lot of fear about what I’d published. I would forever be someone with a serious mental illness. (I’ve since recovered and am now forever the person who had a serious mental illness.)

And disappointment and doubt. I was trying to improve the mental health system by exposing its diagnoses for what they are: flimsy at best and destructive at worst. Pathological showed—through meticulous research and reporting—that they’re scientifically invalid (none can be proven to exist outside of the patient’s mind and a psychiatrist’s opinion) and largely unreliable (two mental health professionals seeing you at the same time, with the same information about you, will likely give you two different diagnoses). But Pathological came out during the pandemic when the media reported (and regurgitated) one mental health narrative: get a diagnosis, get your children a diagnosis, everyone needs a diagnosis. Surprisingly, mental health professionals agreed with and supported my book, but the public didn’t want their diagnoses questioned.

Doubt set in. I started to question my book. My frantic need for more press and sales and the inability to appreciate what I had came from wanting to be reassured that my book was—what? Good? Appreciated? Valuable?

No amount of press can give that to a writer.

None.

My ideal agent recently told me the secret to having a bestseller: Zeitgeist. That’s it. You can write and publish the best book in the world, maybe even get all the “right” publicity, but if the zeitgeist isn’t with you, it won’t sell.

This is incredibly comforting to me. Pathological will have its day. Psychiatry’s flawed diagnoses have come in and out of fashion for over a century. Once people realize their diagnoses are merely a signpost and not the path to mental health, they’ll tire of them too. They’ll start to wonder about healing, not maintenance and identity. The zeitgeist will be with me and my book.

And if it doesn’t happen, I’m fine with that too.

Your Turn:

When did you want something, so badly it hurt but when you got it, everything changed within?

Bonus points if you frame it in a scene.

Post in the comments.

Next week, an interview with Sarah where we dive into her structure, artistic choices and what it was to take on the monster of the medical establishment. You’ll be surprised by what she shares.

Thanks for being with me and please, share this post. Pathological deserves to be shouted out.

🐦⬛, Jennifer

Your Turn:

When did you want something, so badly it hurt but when you got it, everything changed within?

Bonus points if you frame it in a scene.

Post below...

This is encouraging for any writer but it appears she had no luck securing an agent until becoming intimately involved with the industry. I checked her bio. Writing for Time, The New York Times, and The Atlantic couldn't hurt. As well as teaching writing as a professor at Northwestern (!). If this is the path to agents, the rest of us are sunk : )